Spring Play

Medea:

Adaptation conjures ancient mood while focusing on a contemporary divorce

Medea, by Euripides and adapted by writer Rachel Cusk, cuts to the heart of gender politics. The play brings one of world drama’s most infamous characters to controversial new life.

Oxford Theater presented four performances in late February in Tarbutton Theater. Nick Fesette, assistant professor of theater studies, and the play’s director and sound designer had been interested in Medea for a long time.

“By the end of the Euripides play, the audience fully understands why Medea does this horrible thing to her family—i.e. kill her children,” Fesette says. While the audience doesn’t necessarily accept or condone it, the play is structured in a way that helps them grasp the logic behind the murders and feel empathy toward the perpetrator, he adds.

“She’s a female outsider trapped in a patriarchy hell-bent on using and abusing her, tethered to a man who expects her to suffer in silence,” Fesette emphasizes.

Cusk includes all of Euripides’ characters, including a chorus of women who comment on the action, but she fundamentally re-thinks their traits and relationships in sometimes autobiographical ways.

“I’m very interested in approaching topics like crime and violence from this social perspective. I’m interested in stories that eschew narratives of inherent evil and pathology, and instead depict violent crime as the result of situations that anyone might find themselves embroiled in.”

Suffused with the performance energies and formal conventions of ancient Greek tragedy, Rachel Cusk’s adaptation drastically revises its source text and focuses on a contemporary divorce.

First performed in 431 B.C., Euripides’ Medea dramatizes the horrific dissolution of Jason and Medea’s marriage. Fessette wanted to do a contemporary version of the play because he felt that watching the ancient Greek version would feel too removed from the audience’s current lives.

“I think it’s important to check in with the old stories—the myths that still undergird our experiences today. Reflecting on old stories gives us a better sense of ourselves today, and helps us sort out how we might want to change the world for the better.”

— Nick Fesette

Fesette believes the play was provocative to many audience members.

“The play stirred up some not entirely pleasant emotions and also raised questions that aren’t easily answered. It’s difficult to watch a family fall apart while no one does anything to save it.”

Jessie Rivers, technical director of theater, designed the play’s scenery and lighting. She also oversaw the student set building crew. Students make up the cast and technical crew led by Fesette and Rivers.

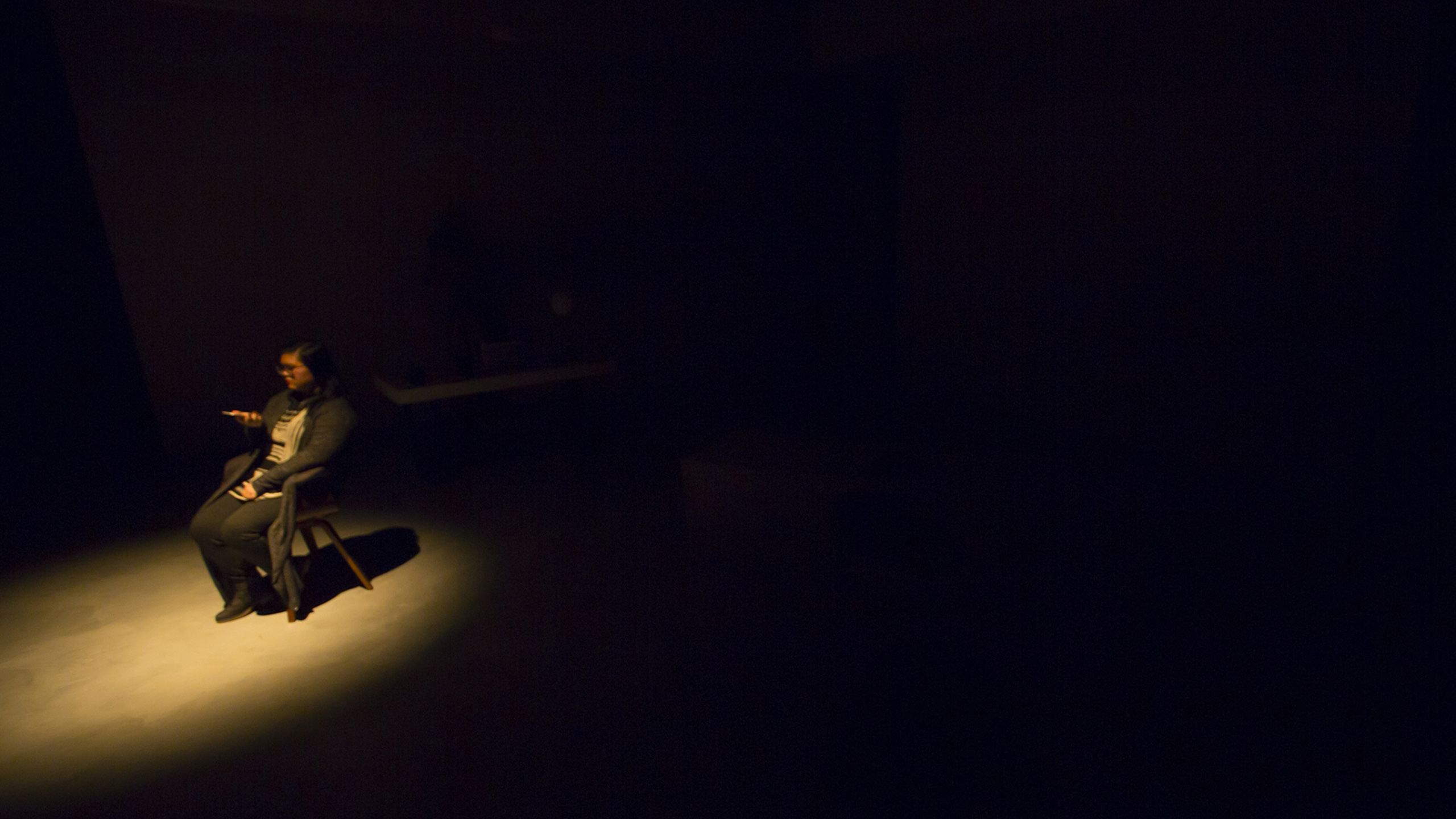

The cast and crew re-staged the drama in a concrete nowhere that exists sometime in the present, amidst multiple ruins. The lighting design switched between realistic and white lighting to feature a range of evocative colors. The set conjured different moods using color.

Drawing on her own fraught experiences with divorce and motherhood, Cusk explores self-doubt and ambivalence about parenthood.

The student actors in the play included Bridget Barnsley, Seger Bayer, Sonia Chang, Zoe Coblin, Cory Dorfman, Edith Kwon, Anna Lindquist, Madison Martin, Natalie Mason, Isabella Montealegre, Rhiannon Moore, and Amanda Przygonska.

Student crew members included stage manager: Maggie Whittemore; assistant stage manager: Royce Flacker; costume designer: Katy Munroe; light board operator: Noah Walton; sound board operator: Sophia Tufariello; scenery construction: Jeremy Cai, Ceci Chen, Talyn Fan, Daisy Geng, Kailey Graziotto, Catherine Hay, Alice Hou, Edith Kwon, Daniel Li, Annie Luo, Melody Ma, Prue Nkansah, Michael Roberts, Stefanie Rogers, Jonathan Russo, Margo Shen, Luke Sims, Toni Sun, Mackenzie Temple, Sophia Tufariello, Arturo Varela-Larrainzar III, Noah Walton, Tony Wang, Sydney Webb, Ethan Wesselkamper, Maggie Whittemore, Helen Xu, Owen Yang, and Tina Zhan; and marketing team: Alexis Jenkins, Mackenzie Temple, Emie Ung, and Emme Van Doorn.

Two young community members, Benjamin Parson and Aiyden Rivers, also joined the production.

Cusk’s play makes an argument that is both unsettling and compelling: that our most treasured personal connections aren’t held together by the bonds of love, but by a tenuous network of fictions.

“A family exists because its members tell stories about it existing. If someone in a family stops believing the narrative, then the whole structure crumbles, and the children, especially, will come to fatal harm. It’s not a pleasant thought, but it makes for interesting drama.”

As Medea’s marriage and social position disintegrate, so too does the play’s relationship with realism. In the end, the entire world of the play magnifies Medea’s surreal and fractured sense of her life. Medea then writes a new bloody reality into existence, a new life written on the wreckage of her family, but a life that is hers alone.

See more about Arts at Oxford and Oxford Theater.