Catherine Bagwell on Making Friends

Catherine Bagwell, Oxford professor of psychology, explores children's social development as her area of research expertise. Emory Magazine recently asked her about how to help kids be good friends.

“I was drawn to the challenge of studying empirically something that is such an important part of our everyday experiences,” Bagwell says. “Throughout childhood and adolescence, we spend much of our time in the company of peers, and children’s social worlds are complicated and fascinating. There is good evidence that friends and friendships can have profound effects not only on social and emotional development but also in domains such as mental health and academic adjustment. Ultimately, a better understanding of the role of peers and friends in children’s lives may aid in the development of interventions to help children who are struggling.”

Five Ways To Help Kids Be Good Friends

#1 Don’t trivialize.

Parents should recognize that children with good friends have many advantages. They are less lonely and less likely to be depressed; they are more engaged in school and cope more successfully with school transitions; and they are more socially competent than children without friends or with lower-quality relationships. High-quality friendships enjoy many positive features—companionship, closeness and intimacy, help and support, loyalty and security—and are associated with positive outcomes. It often takes just one close reciprocal friendship to make a positive difference.

#2 Role model.

In early childhood, parents can explicitly teach social skills that are essential in getting along with peers—how to cooperate and share, how to manage conflict, how to be a good listener, how to be a fun playmate. As children age, parents can be an important sounding board for youth to talk about their friendships and inevitable challenges.

#3 Stay focused.

In adolescence, parental monitoring of peer activities is important for positive outcomes—knowing who their friends are, where they hang out, how they spend their time, and what they’re doing online. Recent work by psychologist Marion Underwood and colleagues shows that adolescents who had conflict with peers online experienced psychological distress. However, adolescents whose parents monitored their activity on social media were less distressed from this conflict than those whose parents did not.

#4 Besties, not bullies.

The excuse that “kids will be kids” is not an appropriate response to bullying and peer victimization. Parents need to send the message that bullying and being a bystander to bullying are never okay. Peer victimization affects between 5 and 30 percent of children and adolescents, and being the victim of peers’ aggression, including physical and verbal aggression as well as social exclusion, is linked with problems such as depression, anxiety, delinquency, and poor school and academic adjustment. On the bright side, having a close friend—an ally who sticks up for you and provides emotional support—is protective.

#5 Watch ‘frenemies.’

Psychologist Amanda Rose coined the term “co-rumination” to describe a communication pattern that involves two friends focusing on a problem, rehashing it, dwelling on the negative effect, and failing to engage in more active and productive problem solving. Having a nuanced understanding of children’s relationships with friends—their benefits as well as their challenges—will help parents help their children establish and maintain healthy friendships that can contribute to social, emotional, and cognitive development and well-being.

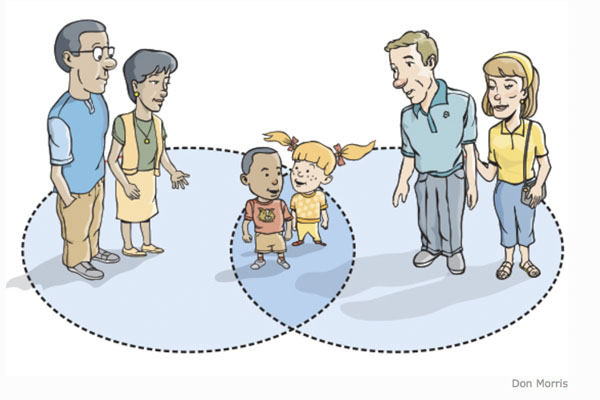

Early friendships are among the first experiences that breach the perimeter of parents’ careful control. Catherine Bagwell, professor of psychology at Oxford College, studies children’s social development, especially the significance of their relationships with peers and friends. Her research asks: How do friends contribute to children’s and adolescents’ development and psychosocial adjustment concurrently and over longer periods of time? Are there ways in which friendships can be maladaptive? Can friendships serve a protective function, for example, against negative outcomes associated with depressive symptoms?

Early friendships are among the first experiences that breach the perimeter of parents’ careful control. Catherine Bagwell, professor of psychology at Oxford College, studies children’s social development, especially the significance of their relationships with peers and friends. Her research asks: How do friends contribute to children’s and adolescents’ development and psychosocial adjustment concurrently and over longer periods of time? Are there ways in which friendships can be maladaptive? Can friendships serve a protective function, for example, against negative outcomes associated with depressive symptoms?

“I was drawn to the challenge of studying empirically something that is such an important part of our everyday experiences,” Bagwell says. “Throughout childhood and adolescence, we spend much of our time in the company of peers, and children’s social worlds are complicated and fascinating. There is good evidence that friends and friendships can have profound effects not only on social and emotional development but also in domains such as mental health and academic adjustment. Ultimately, a better understanding of the role of peers and friends in children’s lives may aid in the development of interventions to help children who are struggling.”

FIVE WAYS TO HELP KIDS BE GOOD FRIENDS

#1 Don’t trivialize.

Parents should recognize that children with good friends have many advantages. They are less lonely and less likely to be depressed; they are more engaged in school and cope more successfully with school transitions; and they are more socially competent than children without friends or with lower-quality relationships. High-quality friendships enjoy many positive features—companionship, closeness and intimacy, help and support, loyalty and security—and are associated with positive outcomes. It often takes just one close reciprocal friendship to make a positive difference.

#2 Role model.

In early childhood, parents can explicitly teach social skills that are essential in getting along with peers—how to cooperate and share, how to manage conflict, how to be a good listener, how to be a fun playmate. As children age, parents can be an important sounding board for youth to talk about their friendships and inevitable challenges.

#3 Stay focused.

In adolescence, parental monitoring of peer activities is important for positive outcomes—knowing who their friends are, where they hang out, how they spend their time, and what they’re doing online. Recent work by psychologist Marion Underwood and colleagues shows that adolescents who had conflict with peers online experienced psychological distress. However, adolescents whose parents monitored their activity on social media were less distressed from this conflict than those whose parents did not.

#4 Besties, not bullies.

The excuse that “kids will be kids” is not an appropriate response to bullying and peer victimization. Parents need to send the message that bullying and being a bystander to bullying are never okay. Peer victimization affects between 5 and 30 percent of children and adolescents, and being the victim of peers’ aggression, including physical and verbal aggression as well as social exclusion, is linked with problems such as depression, anxiety, delinquency, and poor school and academic adjustment. On the bright side, having a close friend—an ally who sticks up for you and provides emotional support—is protective.

#5 Watch ‘frenemies.’

Psychologist Amanda Rose coined the term “co-rumination” to describe a communication pattern that involves two friends focusing on a problem, rehashing it, dwelling on the negative effect, and failing to engage in more active and productive problem solving. Having a nuanced understanding of children’s relationships with friends—their benefits as well as their challenges—will help parents help their children establish and maintain healthy friendships that can contribute to social, emotional, and cognitive development and well-being.