Twin Memorials Working Group completes ‘learning journeys,’ prepares to engage community

The Twin Memorials Working Group is beginning the community-engagement phase of its charge to establish twin memorials on the Oxford and Atlanta campuses to honor the lives of enslaved individuals who helped build Emory’s original campus and others who have historic ties to the community. A newly established website provides historical context as well as updates on the project and will be the locus for Emory and community members to provide input.

In the coming months, public meetings will be held for students, faculty, staff and neighbors, including members of the descendant community, to share concepts for the memorials. The first sessions, which will involve the Covington and city of Oxford communities, begin Feb. 3. Atlanta-based meetings will begin two weeks later. (See block below story for initial dates, times and locations.)

Posing questions, seeking knowledge

Someone with a head start in thinking through these matters is Rev. Avis Williams. A four-time Emory alumna and member of the descendant community associated with Emory’s origins, she recalls a statement an architect made about the forced exodus of enslaved people from their homelands by ship. “The only witness was the water,” the architect said.

Williams — a pastor, member of the Twin Memorials Working Group and a consultant to Baskervill, the firm guiding Emory’s community-engagement and design process — is grateful that bearing witness now invites us all into that process.

But she admits to having many questions about building a memorial to honor the labors of the enslaved, including “How do we design something that celebrates life but honors the dead? And as our students and faculty continue to peel back layers on Emory’s history, how do we memorialize something we haven’t fully grasped?”

Her openness reflects the spirit evinced by the co-chairs of the Twin Memorials Working Group — Douglas A. Hicks, dean of Oxford College and William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Religion, and Gregory Ellison II, an Emory College of Arts and Sciences alumnus and associate professor of pastoral care and counseling at Candler School of Theology.

In July 2021, Hicks and Ellison talked about the value of a “learning journey.” The idea, says Ellison, was “how could we learn best practices from descendants, scholars and administrators at peer institutions so as not to duplicate some of the challenges?”

As Hicks describes it, “We wanted to hear all we could about engaging the descendant community. They are absolutely vital.”

Beginning in the nation’s capital

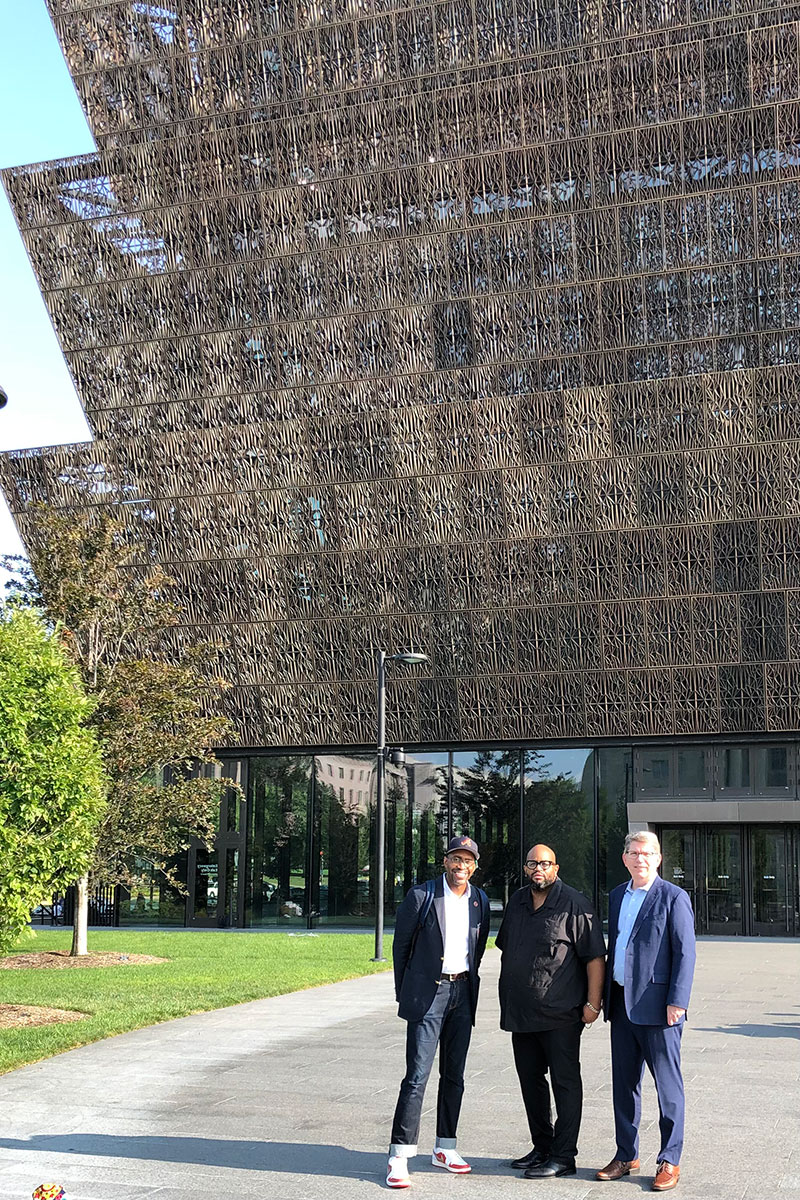

Their first stop was the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where they met Eric Lewis Williams, the curator of religion, who helped them understand what needed to be done to bring this kind of institution to the national mall.

At the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., Ellison (left) and Hicks (right) learned from Eric Lewis Williams (center), the museum’s curator of religion, about the importance of architectural design to narrate history.

One key component: sanctifying the ground itself. “There needed to be healing on those grounds before the museum was actually constructed,” says Ellison. Curator Williams described people from around the country coming to the proposed site to meditate and pray.

Ellison and Hicks both are religious studies scholars. As such, says Hicks, “we are called to think about ritualizing every step to name the spaces as sacred and to honor the lives lost. The sites we visited, and what Emory will eventually create, are sacred spaces and pilgrimage sites. To lift that up is important to the process.”

The response of peers

Next stop was Georgetown University, where they met top administration officials. Prior to 2016, the university had acknowledged that enslaved people who belonged to Jesuit priests were sold to plantations in the Deep South to secure the university’s future. It took a New York Times article to foreground the issue not only for Georgetown but every university with slavery in its past.

The administration’s commitment to the descendant community impressed Hicks and Ellison. Already, Georgetown has provided support for small-business owners and educational opportunities, with the vow that the support will be ongoing, “central to the narrative of the university.”

At the University of Virginia, Hicks called the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers “a marvel” for recognizing the labor of some 4,000 individuals who built and maintained the university. Even where names are not known, the work done by these laborers — “tomato farmer” or “brick mason” — is fully acknowledged.

The final stop was the University of Richmond, where in 2020 its president acknowledged that hundreds of enslaved people had worked on land on which the campus now sits, as revealed by the discovery of burial grounds. The university’s Burying Ground Memorialization Committee is currently engaging members of its campus and descendant communities.

Rev. Avis Williams (back row, second from left) accompanied a class taught by Hicks (far right) to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Rev. Williams also has undertaken several “learning journeys,” traveling to the University of Virginia to talk with descendants and accompanying a class taught by Hicks to the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Although the students on the bus that day were diverse, they were united in asking Williams, as they contemplated the powerful narrative of slavery and lynchings, “How could this happen?”

The role of Baskervill

The Twin Memorials Working Group has partnered with the Baskervill firm for its community engagement and concept design work. One of the nation’s oldest continually operating architectural firms, Baskervill was established in 1897. The Baskervill of today has done work related to monuments and other forms of community remembrance, including William & Mary University’s Memorial to the Enslaved as well as the Richmond Slave Trail and Reconciliation Plaza. The firm has also been involved in the University of Richmond’s Burying Ground Memorialization.

Early in his life, Baskervill principal Burt Pinnock felt the consequence of decisions about monuments. A native of Tuskegee, Alabama, which is predominantly African American, Pinnock describes a monument in the town square erected to Confederate soldiers. The town square is deeded to the United Daughters of the Confederacy “in perpetuity.”

Just out of college, Pinnock started as an architectural intern with Baskervill. Five years on, Pinnock had established one of two African American–owned architectural firms in Richmond. He came back to helm Baskervill in 2015 through a merger with his former firm.

As he thinks about the work with Emory, Pinnock says, “I appreciate that Dean Hicks and Professor Ellison didn’t come with a prescribed idea or process. For me, that also reflects sincerity and openness.”

Ellison notes, “In doing this work over the course of his career, Burt has sometimes been involved in volatile, hard conversations. He knows what he is doing.”

“We want to open up a robust dialogue at Emory so that everyone has an opportunity to express what the concept of twin memorials means to them. The result should reflect the hopes of everyone who provides us input,” says Pinnock.

Community Engagement Dates

Thursday, March 3: Virtual Focus Group (all communities welcome), 6:00–7:30 p.m., Zoom link provided upon registration

Wednesday, March 16: Student Focus Group, 7:00–8:30 p.m., Cox Hall, 3rdFloor

Thursday, March 17: Faculty Focus Group, 2:00–3:30 p.m., Woodruff Library, Jones Room

Thursday, March 24: Virtual Focus Group (all communities welcome), 6:00–7:30 p.m., Zoom link provided upon registration

Thursday, March 31: Student Focus Group, 11:30 a.m.–1:00 p.m., Student Center, lunch provided

Thursday, March 31: Staff, Faculty, and Student Focus Group, 3:30–5:00 p.m., Woodruff Library, Jones Room

To RSVP and for additional updates, check the Twin Memorials website for frequent updates.